AUGUST and Jemima Stehli

AUGUST and Jemima Stehli

18 January - 13 March 2020

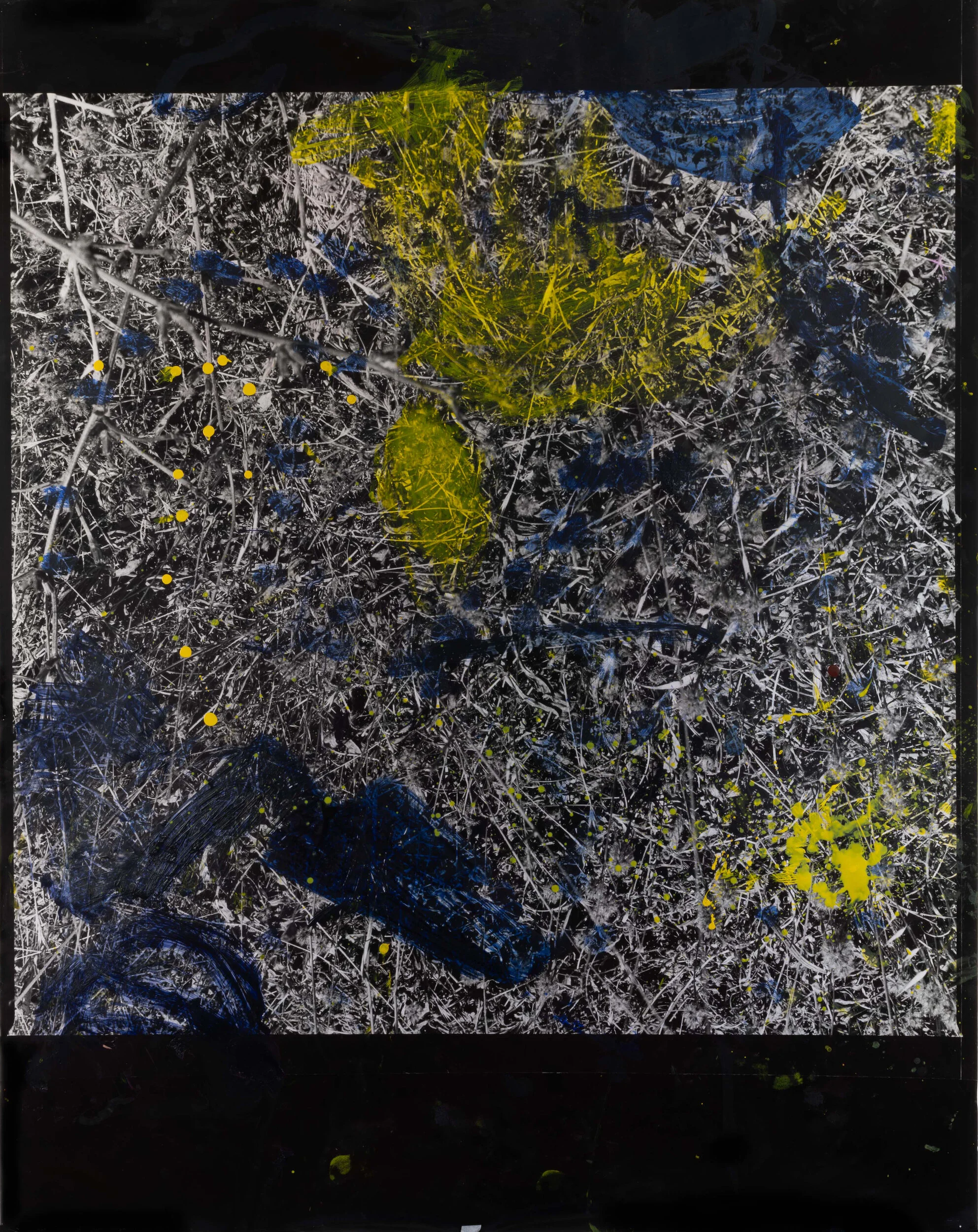

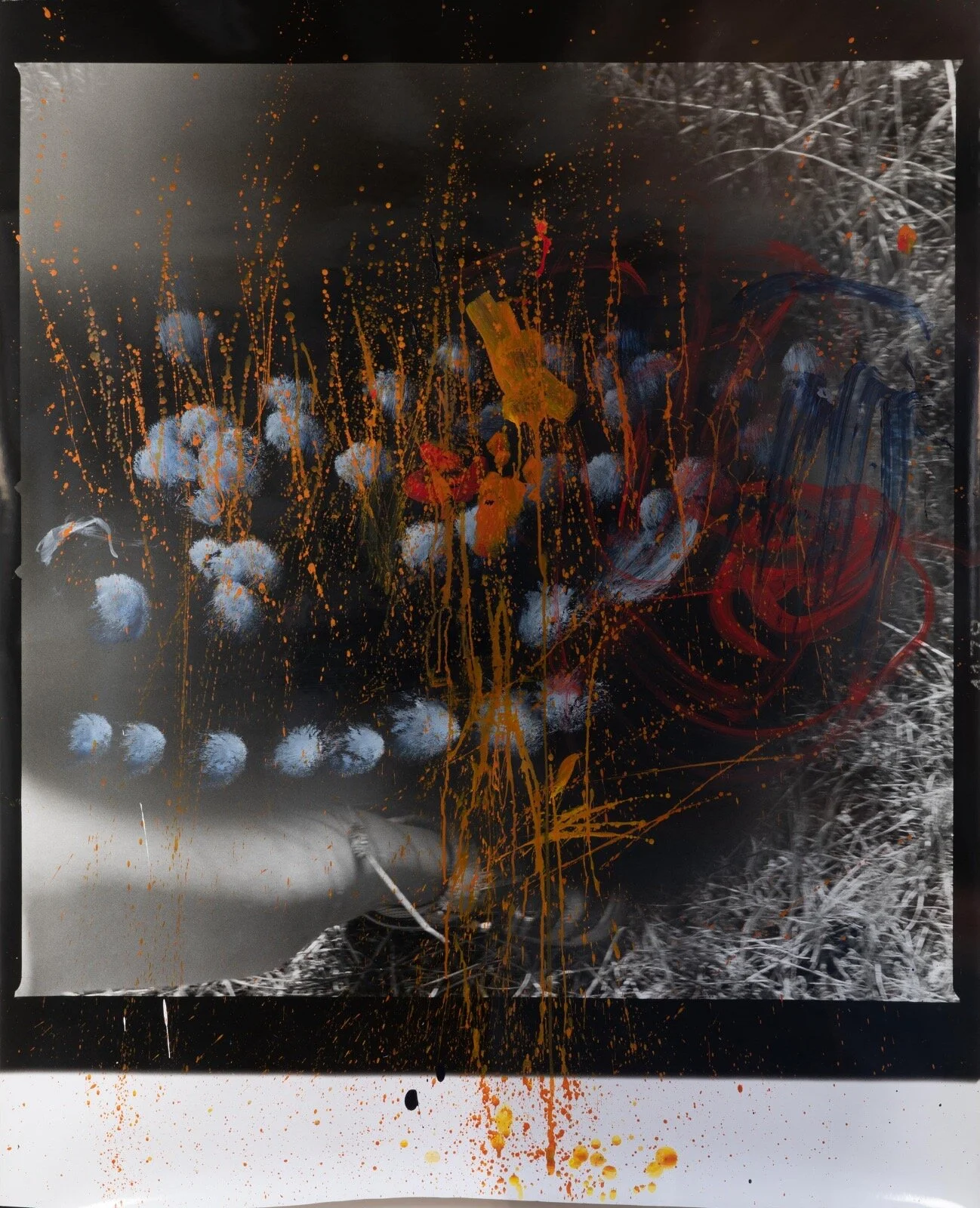

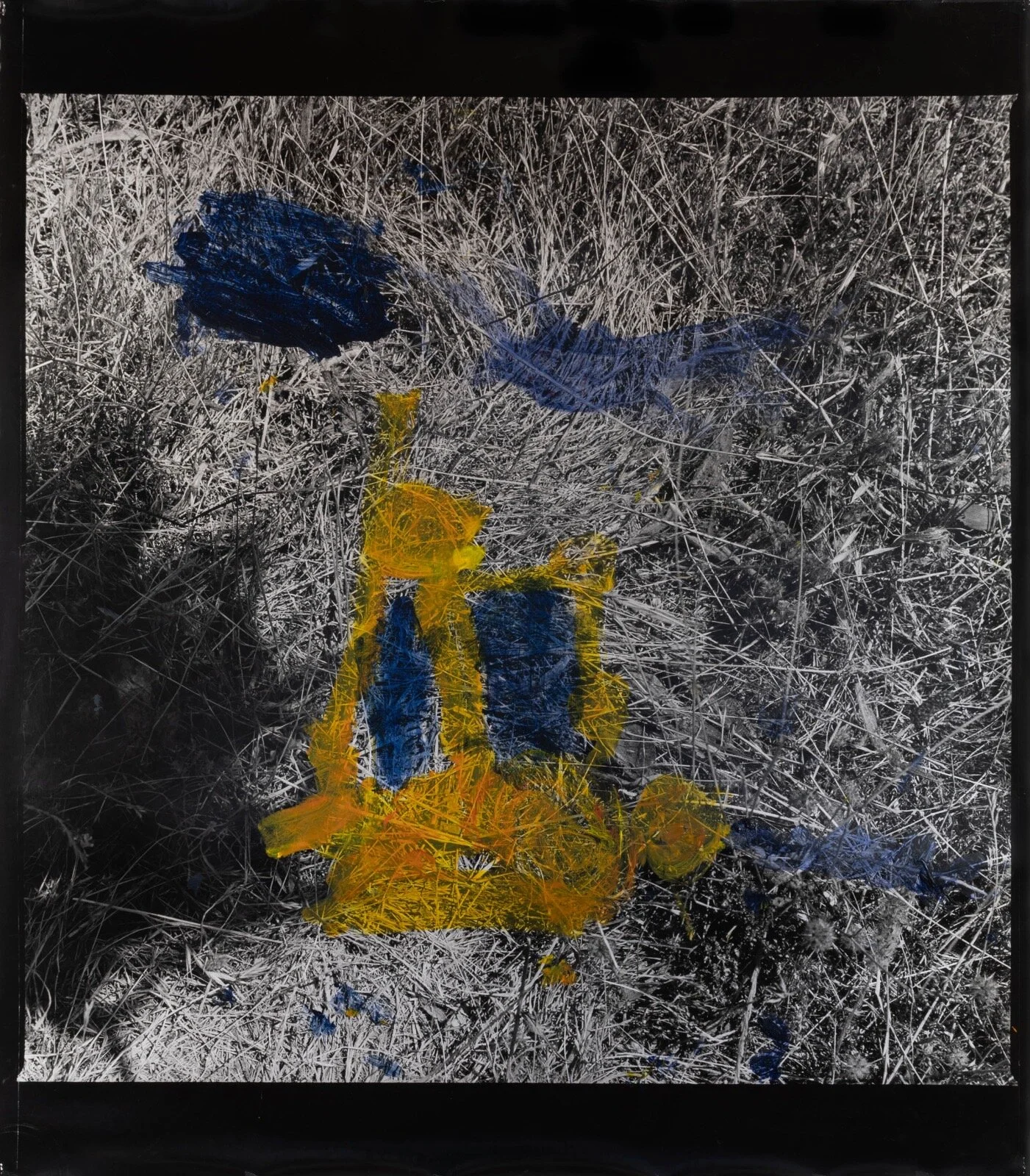

In these new works the bold and irreverent painting by her five year old son August over the surface of large scale black and white photographs describes the proximity, complexity and unpredictability of this living relationship and of the act of making. Jemima Stehli collaborates to both disrupt and generate the image. Some of the photographs are Stehli pregnant, others are landscape close-ups made in the years before and since August’s birth.

—

Excerpt from interview published in conjunction with the exhibition AUGUST and Jemima Stehli

In your ‘Strip’ photographs, the body is so apparent, whereas in these, by introducing the landscape, you disappear into the landscape and August comes in. When did the landscape come into your work?

J: It was when I was travelling with the guys. We were travelling around Portugal, the landscapes became a way in which I could escape and make something that I was absolutely in control of. I’d been introduced to this Hasselblad camera when I did a residency in Australia. I had always worked with a Mamiya 6x7 before that. They only had the Hasselblad, the other one wasn’t working, and I was like, oh, I don’t need that fancy camera. But the minute I picked it up, it was amazing I love the way the square format emphasises the camera frame. I made these very claustrophobic images staring straight at the ground, which were about me having compositional control, which I didn’t have with the band. I was filming them and seeing stuff and getting close to something, but it was always out of reach, and it was always about to fall apart that search was the point of the filming. But the landscapes were absolutely in my control. Then I printed them very heavily to increase the idea of them being a photograph, reducing those romantic relationships to the landscape.

Photographing the landscape was one thing I thought I could manage when I had a child, but that was impossible in fact. When I did try, August was fascinated. A child has to be with you all the time, which most people know, but to me I really wasn’t prepared for that. To begin with he was quite portable, but he was never out of my way. So if I was doing something, he’d want to see what I was doing, so those images are about him getting in the frame and obliterating my image. The photographs of me pregnant were taken by his father and I wasn’t quite sure what I was doing with those. Later, I had this idea about him working, when he was playing I was always recording him working. In a way he was always making stuff and making situations. I’ve got a whole series of sculptures that he’s made, which I could have included, but I’m not even sure how it came, the drawing on top of things. We used to do a lot of drawing together, and it came to the point where I wanted to be in the studio and he wanted to be in the studio.

Did that bring you back to the studio? How long had the hiatus been?

J: I hadn’t been in the studio for years; all the years I was working with the musicians I hadn’t been in the studio. I would use it just to plan a show, but I wasn’t really working in it. I had done those much earlier works, like the ‘Strip’ works—they came out of a much clearer studio practice. After being in Lisbon and travelling with the musicians, there was something quite attractive by that point of being forced to be in one place again.

How did you come to the idea of him drawing over the photographs?

J: I really don’t know. There was already that layering going on, when I was trying to take the photographs and he’s in the frame and I’m there in the shadow, and sometimes he sort of obliterates the image altogether. There’s a parallel between that and how I’m behind the frame with the musicians, but present in the hand-held camera.

He was always painting, so it also became a way to insert his work. He’d got a little bit older and he was a bit more aware of me taking pictures and I was always taking pictures in the same place with the grass and stuff, and he started to do his stuff. So in the end I was taking pictures of him and he was setting things up, and there was this dialogue with the cameras. He was working with a digital camera and I with my analogue and there’s this to and fro.

It could be interesting to show those together.

J: Yeah. I’ve got a whole pile of other things, which are his constructions. I felt like I was interested in his relationship to making, and he could do all this stuff that was formally very beautiful some of the time, and completely free of any sophisticated, formal language, and that to me was really interesting. I guess I wanted to have some of that in the work. I think what I’m trying to figure out with them is that relationship between a destructive and a generative process, and I think they’re both the same thing really. I think that’s what I’ve always worked with as well. When involving other people in the work, I don’t always know what’s going to happen, and there’s a point at which it could all fail. I think I probably enjoy control and I have very fixed ideas, so having that disrupted all the time is quite challenging and very hard work. The hard work for me was having to restrain myself when August was painting and not go, ‘Oh, that’s a lovely bit, just leave it.’