Keith Coventry

Keith Coventry

25 November 2017 - 28 January 2018

Frames of Reference

Pey Chuan Tan

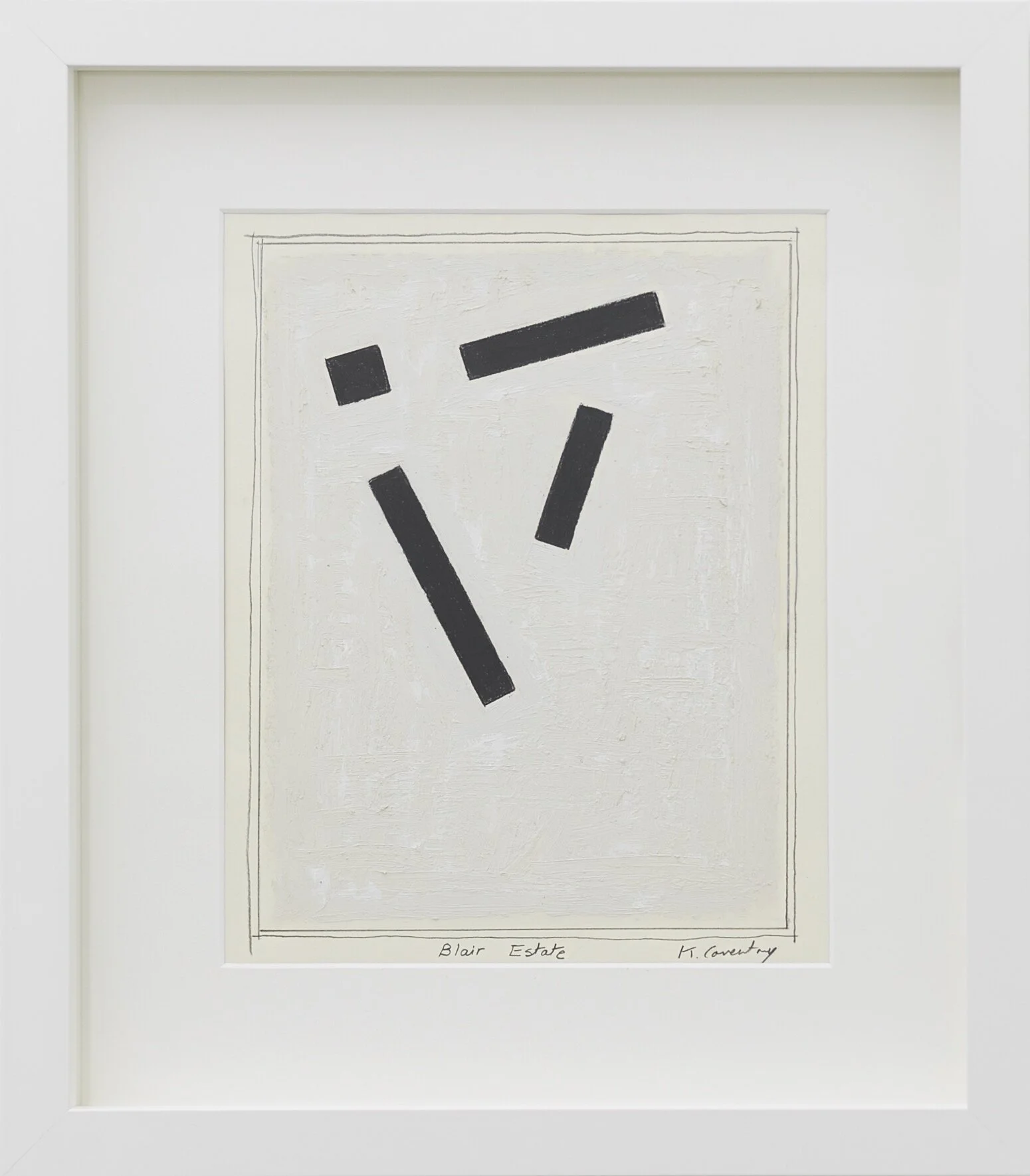

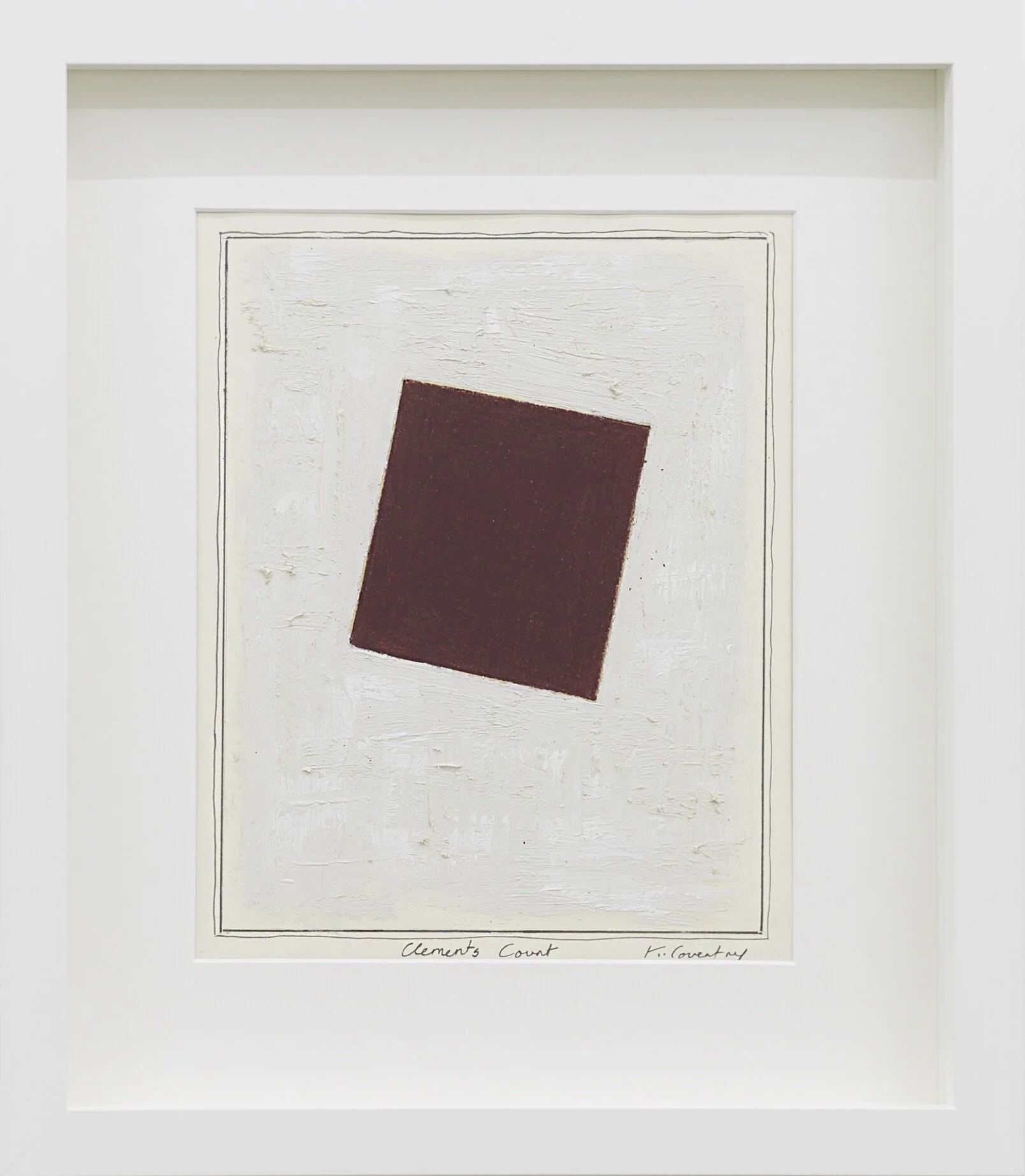

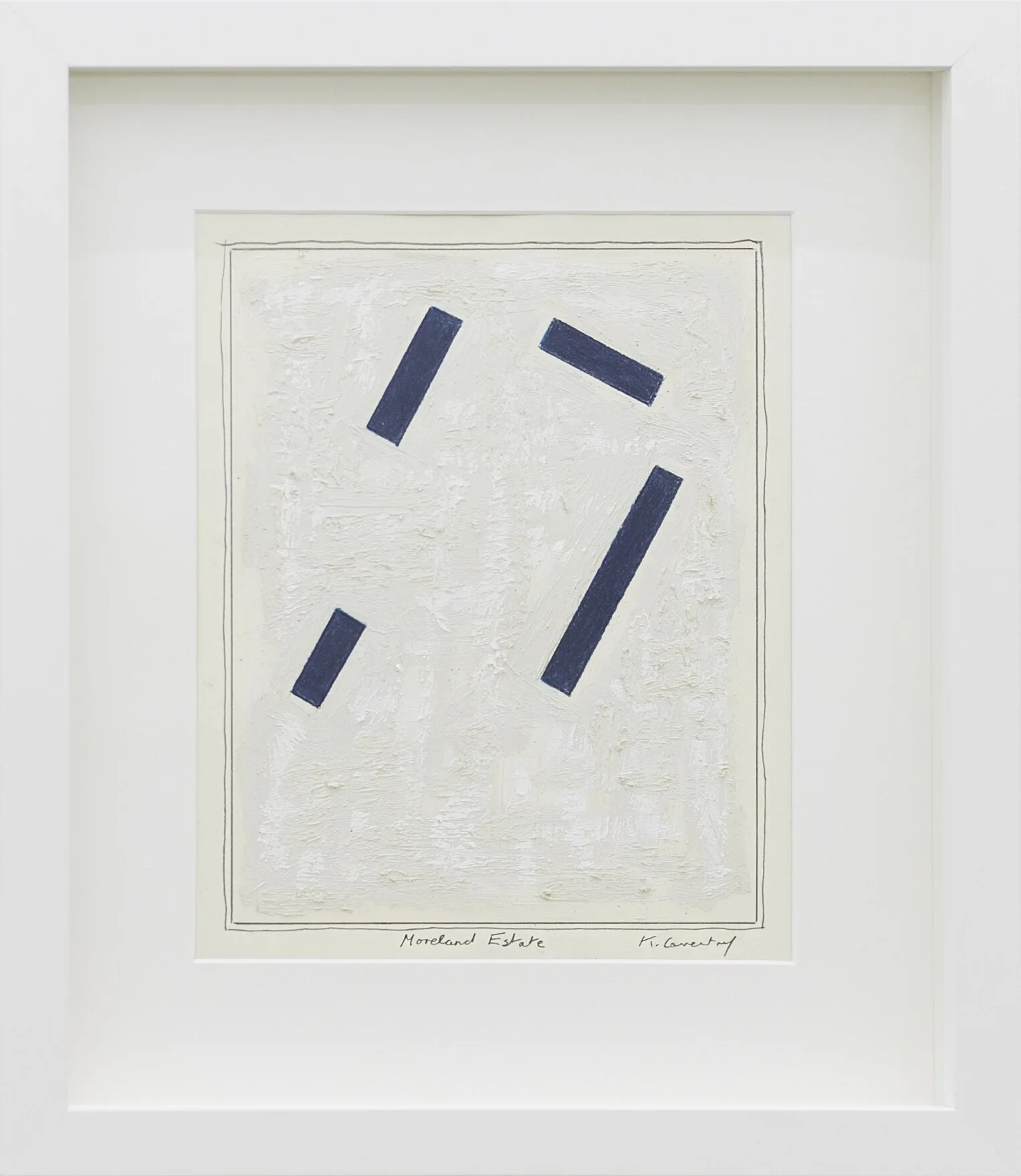

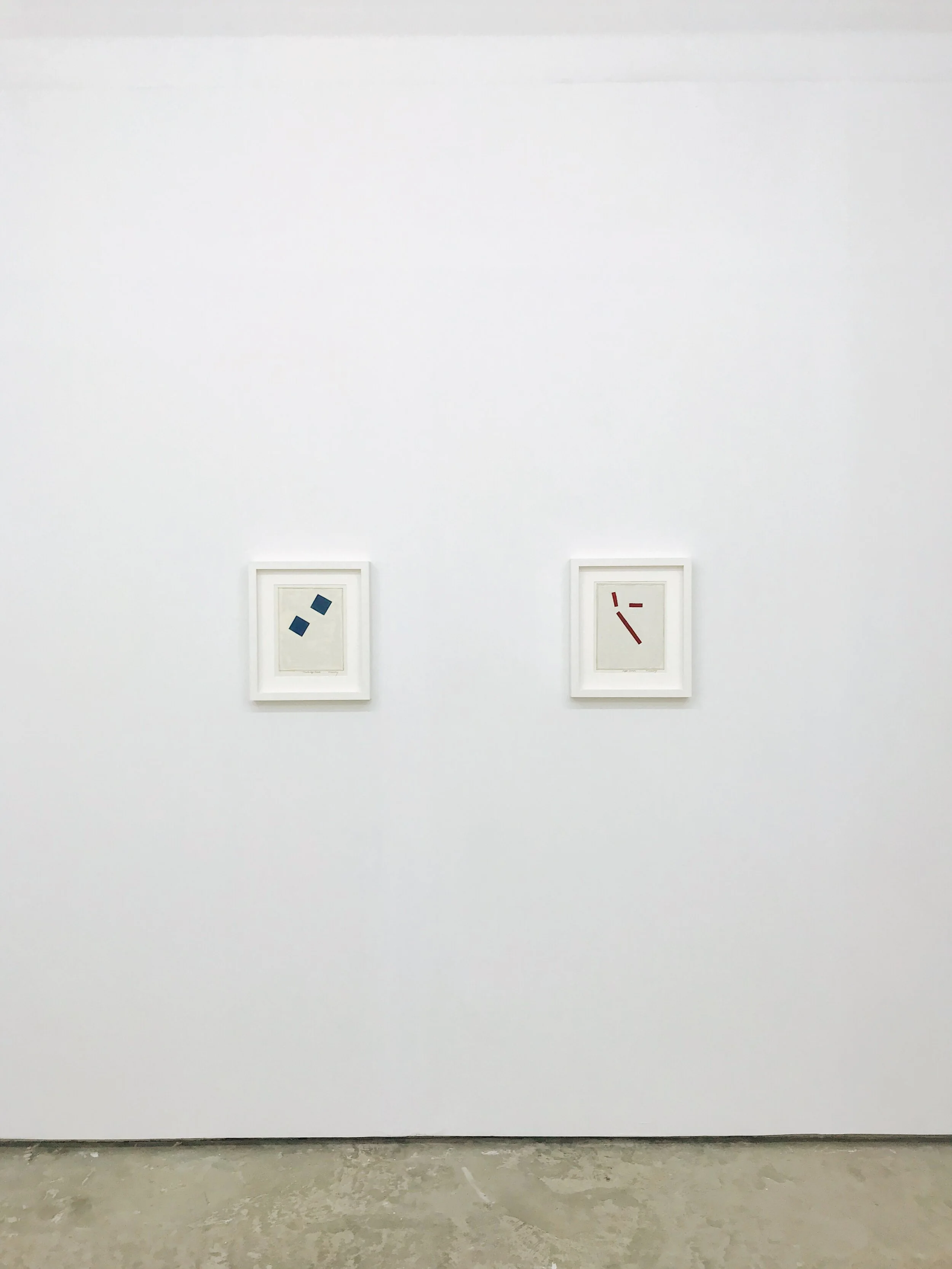

A cursory glance at Keith Coventry’s Estate Paintings provides us with a few details. Here lies a series of hard-edged, abstract compositions, neatly labeled and encased in pristine box frames. The overall presentation isn’t radical by any means, but it readily assumes the conventional appearance of a modern art exhibition.

And then suddenly you begin to realise there’s something else going on here. This isn’t just a simple display of modernist ‘inspired’ paintings, or reproductions of second-tier historical masterpieces. Each composition is in fact a replica of housing compound layouts, commonly found on the entry signage at various council estates in London. Naturally, the title of the artwork takes after the name of its documented location, if only for posterity’s sake.

Much has been written about the stylistic references within the Estate Paintings. The flat, abstract blocks bring to mind the primacy of Russian Suprematist paintings from the early twentieth century, and to some extent, the rhythmic compositions of De Stijl, which originated during the same period. Both movements stood for progressive thinking in the wake of the First World War; De Stijl sought a new universal language befitting the spirit of the modern era, whereas Suprematism claimed to be superior to all art of the past, achieving ‘pure feeling and perception in the pictorial past.’

Coventry meticulously traces the layout of these estate maps, every so often reorienting the compositions or simplifying their outlines. Like Malevich’s Black Square, the Estate Paintings remove all iconography of the real world, leaving you to contemplate the state of the macrocosms before you. It’s interesting to note that since Coventry began the series over 20 years ago, many of the depicted estates have already been demolished. The surviving estates are a far cry from the utopian ideals of their original Modernist architects, which espoused better living in clean, high-rise buildings with plenty of fresh air. Neglected and outmoded in their present state, many are criticized as being breeding grounds for a myriad of social ills.

Framing creates an illusory effect here, and each of these white boxes seem to signify the composition as a work of art that’s worthy of attention. Coventry cleverly references the lofty aspiration and aesthetic of high modernism, playing into the symbolism of the rarefied cultural artifact, before turning it on its own head and exposing the gritty realities of modern life. Depicted from an aerial perspective, the Estate Paintings represent not just the compacted issues of high-density living, but also collapsed histories and ideologies – the slow unraveling of modernist ideals, interpreted through the vernacular of modernism itself.

To capture abstract beauty in such a prosaic source requires both social cognizance and a particularly dry, covert sensibility. Coventry’s catalogue of council estates, kebab shops, and fast food chains addresses sociopolitical attitudes that are decidedly English at times, but for the most part he examines the ontological dichotomies that surround us: abstract and concrete, idealism and materialism, essence and existence. There’s no fiction or illusion in his oeuvre, only sharp observations on the pitfalls of modern life, and some of its inherent cultural absurdities.